Wes Wilson, psychedelic poster pioneer, dies at 82

Artdaily_NEW YORK (NYT NEWS SERVICE ).- Wes Wilson, who helped create the trippy look associated with the second half of the 1960s through the vivid, swirling posters he made for rock shows by the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and others, died Jan. 24 at his home in Leanne, Missouri. He was 82.

His son Jason confirmed his death. No cause was given.

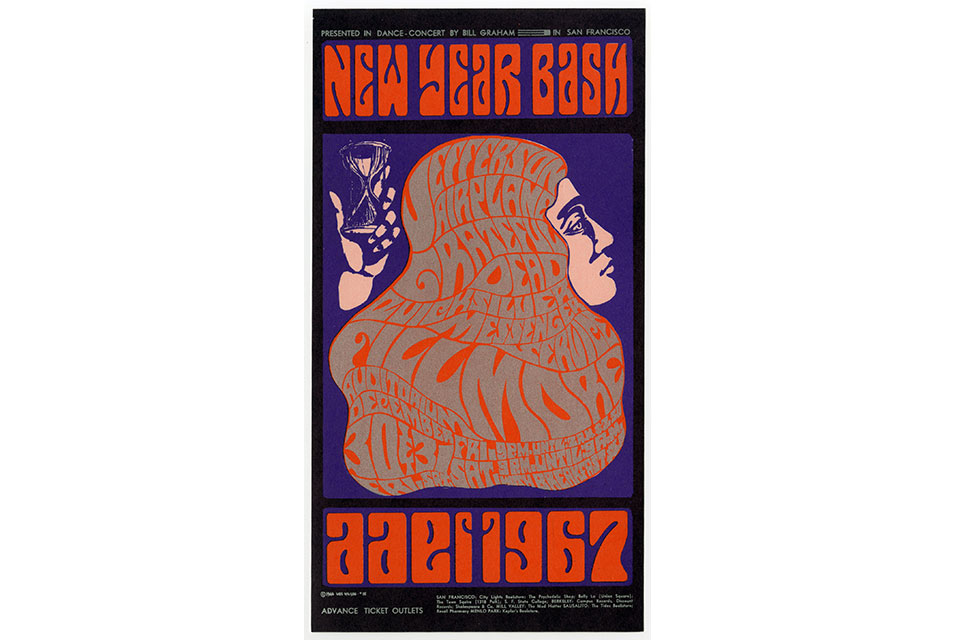

Beginning in 1966, Wilson made posters for Bill Graham, who produced rock shows at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, as well as for Chet Helms of Family Dog Productions, who started at the Fillmore but soon moved to the Avalon Ballroom, not far away.

Posters had been used to advertise stage shows for decades, but most were utilitarian conveyors of date, time and place. Wilson, along with several other poster artists, took the form to a different level, one full of loud colors, attention-getting imagery and vibrant typography.

He was especially known for the free-flowing block lettering on his posters, which he adapted from a font created by Austrian designer Alfred Roller.

“The original type designer had everything on strictly gridded layout (straight lines),” Art Chantry, author of “Art Chantry Speaks: A Heretic’s History of 20th Century Graphic Design” (2015), wrote on Sunday in a Facebook post. “Wes Wilson simply created the same letterforms on a swirling curve and voilà! — ‘Psychedelic Type!’ The world was never the same again.”

If the lettering was often hard to decipher, that was by design. Darrin Alfred, curator of architecture and design at the Denver Art Museum, who curated a 2009 exhibition there called “The Psychedelic Experience,” which included Wilson’s work, recounted a conversation between the artist and Graham about one of his first posters.

“Well, it’s nice, but I can’t read it,” Graham is said to have remarked.

“Yeah,” Wilson responded, “and that’s why people are gonna stop and look at it.”

That arcane quality, Chantry said, also served as a sort of rite of membership.

“The point of psychedelia was that nobody could read it — unless you were part of the ‘tribe,’ ” he wrote. “It was a type of marketing that was trying to (literally) scare away the ‘straights’ (or at least make the secret world illegible to them).”

An early poster that solidified Wilson’s emerging style was for a show at the Fillmore in July 1966 featuring the Association, Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Grass Roots and Sopwith Camel. The names of the groups appeared in bright red-orange against a green background, the lettering suggesting flames. He used a similar look for the cover of Paul Grushkin’s book “The Art of Rock: Posters From Presley to Punk” (1987), except this time the flaming lettering constituted the hair of a blue-colored figure.

Wilson’s posters — collectors’ items today — documented the astonishing array of groups that played the two San Francisco halls as the psychedelic ’60s took hold: Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead shared a bill at the Fillmore in August 1966, Country Joe and the Fish and Buffalo Springfield teamed up there that November, and there were dozens more.

“In those days, for $2, you could see some amazing stuff,” Wilson recalled in a 2006 interview with The News-Leader of Springfield, Missouri, near the farm he moved to in 1976.

It was said that Wilson’s disorienting posters were easily read by anyone tripping on LSD. He himself, he said, never got as wild as many of the concertgoers who were the posters’ target.

“I was far enough out to be an artist,” he told The News-Leader, “but not far enough out to go over the edge.”

Robert Wesley Wilson was born on July 15, 1937, in Sacramento, California, to John and Ethel (Thomson) Wilson. His mother, Jason Wilson said, was an artist.

After graduating from high school Wilson served in the Army National Guard and for a time attended San Francisco State College (now University), dropping out in 1963. A friend, Bob Carr, had a small printing business and made Wilson a partner, doing the layout and design work. Graham and Helms became clients.

But Wilson’s first poster wasn’t for a concert. It was a self-published work, made in 1965, that was inspired by his growing concern over the increasing American involvement in Vietnam.

“I had been in the Army, and so I was kind of on the alert to watch out for our foreign policy,” Wilson told NPR in 2016. “And when we got involved in Vietnam, I began to distrust the establishment of our country.”

The poster he made suggested the American flag, but the white stars were on a blue background in the shape of a swastika. “Be Aware,” the type said. The pressman who usually printed the shop’s material was alarmed when he saw it.

“When he looked at my design his usual smile faded fast,” Wilson wrote in a 2013 blog entry on his website, “and he said something like this: ‘Wow; Wes, you’d better add something else — like maybe ‘Are We Next?’ — or most people just won’t get it.” Wilson took the advice, emblazoning those words across the top, and sold the poster all over San Francisco.

The next year he started making posters for shows, and within a year they began to draw national notice. He was written up in Time and other magazines.

“Expanding like the mind to fill every conceivable bit of space,” Time wrote of his designs, “they are intended to capture the visual experiences of an LSD tripper when, as one hippie puts it, ‘You look at your hand, and it goes in all directions.’”

Wilson’s style influenced Victor Moscoso, Rick Griffin, Stanley (Mouse) Miller and Alton Kelley, who were also making poster art in San Francisco; together they are sometimes labeled the Big Five of the genre. Wilson, though, moved on from posters, working in enameled glass and then in watercolor.

“His watercolors of the ’70s to early ’80s capture some of the same luminosity and space-partitioning qualities of the glass work,” Jacaeber Kastor, who mounted a Wilson show at his Psychedelic Solution gallery in the West Village of Manhattan in 1987, said by email. “His focus shifted to doing portraits, and he mainly chose to portray people he personally found interesting or significant.”

After moving to the Ozarks in 1976, Wilson split his time between making art and raising beef cattle. The 1987 exhibit and other gallery shows rekindled his interest in posters, and for a time he published a journal on poster art and related subjects called Off the Wall.

Wilson’s first marriage, to JoAnn Kimmons, ended in divorce. In addition to his son Jason, who is from his second marriage, Wilson is survived by his wife, Eva (Bessie) Wilson; three children from his first marriage, Karen Borgfeldt, Shirryl Bayless and Kelly Wiedman; two other children from his second marriage, Colin Wilson and Theanna Teodorovic; 10 grandchildren; and a great-grandchild.

Wilson had numerous brushes with rock history, but in 1967 he had a brush with a different sort of history, when the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency commissioned a poster from him for its new office in Los Angeles.

“The manager of this new office at the time was Mr. Bob Haldeman,” Wilson wrote on his blog, “and it was probably either him or his assistant, Mr. Ron Ziegler, who originally spoke with me on the phone about it.” Both, of course, would soon be important figures in President Richard Nixon’s administration.