Beloved for His Popping Pastels, Nicolas Party Takes a Darker Turn

Artsy_Nicolas Party’s inaugural exhibition at Hauser & Wirth will be a bit darker than his past shows, which have been characterized by bright pops of color. This time, he’s drawn inspiration from the 17th-century Flemish artist Otto Marseus van Schriek

, known for depicting snakes, frogs, butterflies, and other creatures living near or on the forest floor. “Sottobosco,” which opens at Hauser & Wirth’s vast Los Angeles complex on Thursday—the same day as the VIP preview of Frieze Los Angeles’s sophomore edition—is centered around the sottobosco subgenre of painting, which focuses on painting the flora and fauna of the undergrowth.

“There’s a movement in the show that’s darker, because the idea behind sottobosco is painting where light doesn’t really go,” Party said. “There’s something interesting about painting things in an environment that’s not well-lit.”

“Sottobosco” marks Party’s first show with Hauser & Wirth since signing with the gallery last year. Marc Payot, president of the gallery, said he was first drawn to Party’s singular style due to the enigmatic and magnetic quality of his imagery, and his anachronistic preference for using pastel. Party’s emulation of Swiss artists, such as Ferdinand Hodler and Félix Vallotton, of course helped. (Payot and Party are both Swiss.)

“When people encounter [Party’s work], they are drawn in by the imagery, his extraordinary sense of color, his sensual but also rather strange forms,” Payot said. “The layers of association to history are certainly there, but the works are quite universal in their visual language.”

In “Sottobosco,” Party updates a centuries-old genre with his stylized approach, crafting the torsos of his subjects out of frogs, mushrooms, roses, and snakes. He also drew inspiration from the nascency of art history: He’s created a mural of a cave to allude to the earliest cave paintings, which, for millennia, were only accessible by torchlight.

Party’s 2017 show at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden wasn’t inspired by art history at all, but rather by U.S. president Barack Obama’s reassuring words on the night of the 2016 presidential election: “No matter what happens, the sun will rise in the morning.” Ruminating on the theme of sunsets, Party painted the circular, glass-walled gallery on the museum’s third floor with setting or rising suns, drawing on the work of art-historical figures like Caspar David Friedrich, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Vallotton.

“It’s a very inclusive approach to art,” said Stéphane Aquin, who curated the Hirshhorn show, of Party’s choice to incorporate allusions to the works of others into his own.

Painting on walls

Party was born in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1980, and his first forays into art had nothing to do with pastels. He dabbled in graffiti in his teenage years, which comes across in the murals he created for “Pastel” (his current show at the FLAG Art Foundation in New York, through February 15th), and for his Hirshhorn show and the upcoming Hauser & Wirth exhibition. Party only has a few weeks to complete his installations for museums and galleries—and mere days if he’s doing one for an art fair—but those tight deadlines don’t feel so challenging compared to his graffiti days.

“You have a very clear time constraint, because you’re going to get caught if you take too long,” he said. He described the process of creating both murals and graffiti as a sort of dance.

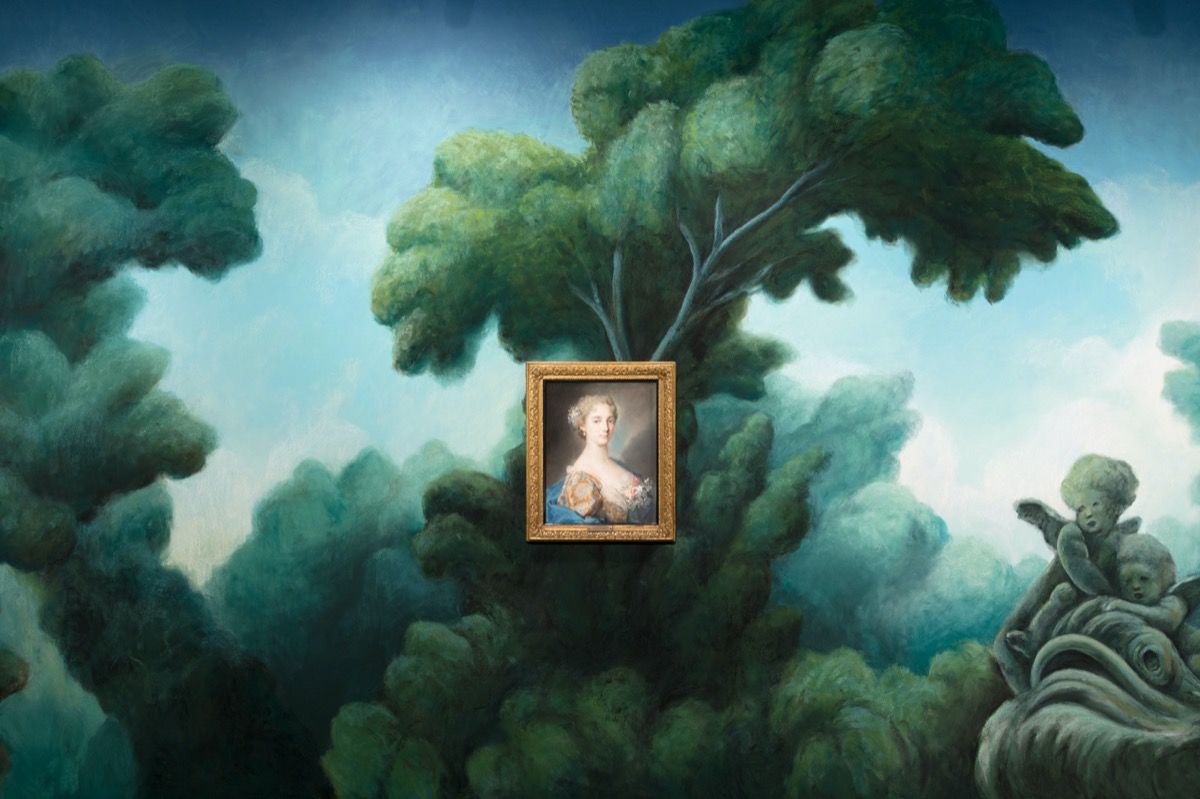

Party combines large-scale murals with arches throughout his installations to create an atmospheric experience; for the FLAG show, he placed an 18th-century Rosalba Carriera

portrait against his own reproduction of elements from Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Progress of Love (1771–72). Narrow archways provided glimpses into other spaces colored in deep pinks, purples, and yellows.

“The use of the color white as a background for paintings is very often damaging to the perception of the object itself,” Party said, pointing out that white-cube spaces in galleries and museums only became the norm very recently. His experience seeing Fra Angelico’s frescoes at the San Marco in Florence informed his decision to bring art and architecture together to create a more powerful viewing experience.

Party described his murals as sets—throwbacks to the days after finishing art school when he and a few friends founded a venue that hosted musical performances. “I never really stopped trying to create an environment where the art is the set,” he said.

Party combines these sets with sculptures and canvases of wide-eyed, colorful, cartoonishly stoic characters. “The androgynous and often sensual nature of his figures and bold use of colors sets him apart,” his longtime dealer Xavier Hufkens said. “You can tell he is enjoying himself.”

Sales party

Party started to turn heads at auction when his painting Landscape (2015) sold at Phillips in May 2019 for $608,000, over four times its high estimate. This impressive feat was closely followed by Hauser & Wirth’s announcement that the mega-gallery was adding Party to its roster. Party has broken his auction record twice more since then, with his current record-breaking work, Rocks (2016), bringing in $1.1 million at a Christie’s auction this past November.

After a number of prominent sales last year, the auction market for Party seems to have cooled off, at least temporarily. His upcoming lot at Sotheby’s contemporary art day sale in London on Wednesday—a boldly colorful portrait in pastel—is estimated to bring in between £60,000 and £80,000 ($77,000–$103,000).

“The images he paints are reminiscent of the work of Surrealists

, but feel like a fresh, different interpretation, which makes them interesting to both established and young collector bases,” said Marina Ruiz Colmer, head of Sotheby’s contemporary day art auction in London.

Party’s prices on the primary market have also jumped higher and higher as his recognition among collectors has grown. His 2018 installation in the Xavier Hufkens booth at Art Brussels—which took the form of a small chapel to showcase his brightly colored landscapes—was a resounding success, with all three featured works selling for figures between €50,000 and €80,000 ($61,000–$98,000). Just a year and a half later, Hauser & Wirth sold a similar pastel work by Party for $385,000 at Art Basel in Miami Beach.

Party’s status as a young artist whose work is commanding higher and higher prices at auction has prompted concerns over whether collectors may “flip” his works—buying them from a gallery and immediately reselling them at auction for a higher price. But many galleries the artist works with have put processes in place to curb this practice.

Hufkens sells works to institutions and collectors with whom the gallery has a longstanding relationship. “I feel that these relationships imply not only mutual trust, but also a genuine passion for the artist’s work and the gallery’s program,” the Brussels-based dealer said.

“We are extremely thoughtful about the placement of the work, focusing on institutions and connoisseur collectors who take the same long view that we as a gallery take,” Payot said, adding that Hauser & Wirth is focused on providing resources to its younger artists so they can explore or expand their practices.

Party said that working with Hauser & Wirth, which has a total of 10 locations around the world, is more like working with a museum than a gallery in terms of the structure and resources available. Nevertheless, he has maintained his representation at five other galleries, including Xavier Hufkens—an unusual move for someone who attracted the interest of a global mega-gallery.

“If you do a show at Hauser & Wirth, people will see your show in a different way,” he said. “Sometimes in a positive way, and sometimes in a negative way.”

Historical perspective

Party’s murals were up at the Hirshhorn for four months, and Aquin found it heartbreaking to paint them over. “When we work in museums, we want to conserve absolutely everything, we’re obsessed with that,” he said. “And that’s not the nature of things, that’s not how history functions.”

But Party’s decision to make murals with pastels is in keeping with his interest in ephemerality over longevity. “You basically paint with dust,” he said. “You can remove the entire surface of the painting by blowing on it.”

In “Sottobosco,” he’s drawing his admirers’ attention to a little-known 17th-century painter, and then back even farther to the earliest recorded paintings—which, in essence, were site-specific murals. Party’s temporary installations appeal to different sensibilities than his highly sought-after works on canvas and paper: They raise the possibility that the most profound art experiences are transitory.