Dale Chihuly, Pioneering Glass Artist and Seattle Icon, Is Building a Major Legacy

Artsy_Dale Chihuly is still building on his reputation as Seattle’s most famous artist, even as tech behemoths Amazon and Microsoft increasingly define Seattle’s cultural landscape. In a city that has rapidly priced out painters and sculptors in need of studio space, Chihuly has established four key complexes that support his business and creativity: the Chihuly Garden and Glass museum; the Boathouse and attached hot shop; a storage facility in Tacoma; and a studio, office, and viewing room in the Ballard neighborhood where he stages monumental work. A lifelong collector of art and assorted objects, Chihuly has, in a sense, collected property itself.

Chihuly, now 78, has been so prolific, financially successful, and widely exhibited for so long that it’s easy to forget how innovative his artistic vision has been. Over the past five decades, he’s pushed a fragile material to awe-inspiring scale and developed an instantly recognizable aesthetic exemplified by spectacular, brightly colored glass installations that suggest natural forms. As the artist’s enterprise continues to expand, his team must consider his long-term legacy.

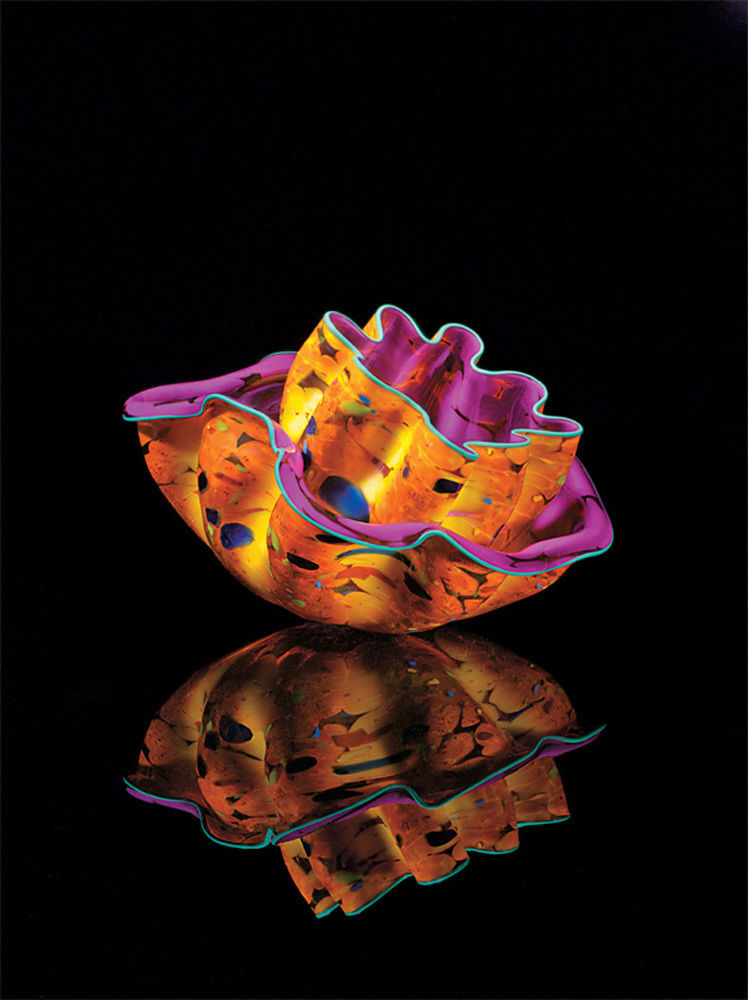

Chihuly’s best-known installations—mounted by museums, botanical gardens, and hotels worldwide—can evoke full-scale, sunshine-yellow trees or multistory towers of aqua and chartreuse curls. His giant, asymmetrical bowls, or “macchia,” resemble seashells, while his “chandeliers”—20-foot-long tangles of blown glass—descend from lofty ceilings.

Over the past five decades, he’s pushed a fragile material to awe-inspiring scale.

Fabricating and selling this ambitious, large-scale work requires significant real estate. Chihuly has built his own wood-paneled showing rooms at his Ballard office, carefully calibrated to meet his aesthetic needs. Clients need not wait for a Chihuly exhibition to see an impeccably curated presentation of the artist’s most saleable work.

Yet the real magic happens at Chihuly’s hot shop, a one-of-a-kind laboratory located just off Lake Union and concealed by an unassuming, industrial gray façade. Beneath a neon sign that reads “NO TELL MOTEL / VACANCY,” there are silver heat-resistant jackets, shelves of colored glass, fire hoses, massive glass ovens, paddles, and chairs. A rainbow of blown-glass baubles and shells hang from the side wall, organized by hue.

One Sunday morning in early February, Chihuly’s team was in the midst of glassblowing at the shop. Head gaffer and long-time associate James Mongrain led assistants as they fashioned a clear glass bowl adorned with delicate white lines that resembled scrawled handwriting. The piece is part of Chihuly’s new, lace-inspired “Merletto” series, which will debut at Seattle’s Traver Gallery this spring (the exhibition runs from May 7th through June 27th). In April, Chihuly will mount a full-scale exhibition at the Cheekwood Estate and Gardens in Nashville, Tennessee. His work is also on temporary view this year at the New Orleans Botanical Garden and the Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens in Columbus, Ohio.

Like a Renaissance master with a workshop of skilled artisans, Chihuly serves as an individual artist, creative director, and public face of his large-scale operation.

Like a Renaissance master with a workshop that employs skilled artisans, Chihuly functions both as an individual artist and as the creative director and public face of a large-scale operation. His wife, Leslie Jackson Chihuly, noted that “Dale never said, ‘I’m going to be the best glassblower in the world.’ He said, ‘I’m an artist.’”

Mrs. Chihuly serves as the president and CEO of Chihuly Studio and Chihuly Workshop. The role is unusual within the context of an artist’s studio; Mrs. Chihuly’s title speaks to the vast aesthetic and financial accomplishments of her husband’s brand. While contemporary artists such as Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami are known for employing dozens of studio assistants—and Andy Warhol, of course, employed an entire Factory—Mr. Chihuly’s footprint has uniquely expanded into public and private arenas. His practice, with the help of around 100 employees, finds its niche at the intersection of art, design, and architecture, and he’s had no qualms about capitalizing on the different commercial channels associated with each discipline.

Mrs. Chihuly, in fact, noted that her team is connecting with Murakami’s Seattle-based staff. “I’m just very curious to know what they’re doing with video, what they’re doing with their publications, what they’re doing with other artists,” she said.

While her husband works in the hot shop, Mrs. Chihuly serves as both a savvy businesswoman and philanthropist. She is on the boards of Pilchuck, the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, and Vassar College, her alma mater. The Dale and Leslie Chihuly Foundation, established in 2009, provides grants to artists and offers glassblowing opportunities for veterans.

Mr. Chihuly, for his part, has long helped to promote glass on both coasts. He led the Rhode Island School of Design glass program for 11 years. In 1971, he co-founded Pilchuck Glass School, just north of Seattle, which helped turn the region into a mecca for glass artists. Mr. Chihuly’s studio itself offers an informal education of its own, as it welcomes artisans both skilled in the medium and just starting out.

The Chihulys have also been active in the fight against stigmas associated with mental health. Mr. Chihuly has suffered from manic and depressive episodes throughout his life. Within the past few years, the couple has spoken publicly about his struggles with bipolar disorder. During my recent visit to Seattle, Mr. Chihuly was feeling too low to speak with press; Mrs. Chihuly, a competitive skier with a soft Southern lilt, served as the face of the studio and a voice for the artist himself.

“Dale never said, ‘I’m going to be the best glassblower in the world.’ He said, ‘I’m an artist.’”

The artist’s physical maladies are a well-recorded piece of his own story: A 1976 car crash blinded him in one eye and a bodysurfing accident in 1979 injured his shoulder, making him unable to blow glass. Since the latter incident, Mr. Chihuly has relied on skilled gaffers, or glass artisans, to perform the extensive physical labor required by the medium. Mr. Chihuly often sketches his concepts, then leaves his teams of glassblowers to interpret and execute. He maintains oversight and can redirect projects as needed.

To complement Mr. Chihuly’s studio output, the Chihulys have shepherded the publication of over 30 films and books on the artist’s life and work. In the mid-1990s, producer Michael Barnard filmed Mr. Chihuly as he prepared for his “Chihuly Over Venice” exhibition, which situated the artist’s work across the sinking city. Recalling another shoot, Mrs. Chihuly noted, “He’s very conscious and very comfortable in front of a camera. He’d play to it.”

While plenty of artists publish numerous monographs and exhibition catalogues, Mr. Chihuly seems to favor accessibility over critical, academic perspectives. In 2016, his team published a book of his faxes, while other volumes focus on his “cylinders” (intricately decorated cylinders with holes at their centers) or glass ikebana (Japanese flower-arranging) constructions.

The book Chihuly: An Artist Collects (2017) exclusively discusses Mr. Chihuly’s collections. He started collecting as a child, bagging and selling glass marbles. Mrs. Chihuly believes it’s only natural for visual artists to “want to be surrounded by things they want to look at.”

In addition to ceramics by Pablo Picasso, an enormous Henry Darger drawing, and more paintings and sculpture, Mr. Chihuly has amassed Navajo blankets; Edward S. Curtis’s early 20th-century photographs of Native Americans in the West; string dispensers; cars; accordions; toy vehicles; antique cameras, radios, and clocks; art books; masks; bottle openers; makeup brushes; matchbooks; and records. Quantity trumps quality. The collections impress with their sheer volume, rather than the objects’ individual merits.

These collections feature prominently at Chihuly Garden and Glass, the museum devoted exclusively to Mr. Chihuly’s artwork. Opened in 2012, the institution ensures that Mr. Chihuly’s output will have a permanent, public, physical space in Seattle. As with all his spaces, Mr. Chihuly directed the interior design and lighting (he doesn’t consider an artwork complete until it’s adequately lit and photographed). “He’s really a frustrated architect,” Mrs. Chihuly said.

Chihuly Garden and Glass sits on public land adjacent to Seattle’s most iconic landmark, the Space Needle. The prime location positions Mr. Chihuly as a local icon, as well. The artist’s Curtis photographs and Navajo blankets adorn one gallery, bolstering the idea that the history and hues of West Coast history have informed Mr. Chihuly’s artwork. In the museum’s Collections Café, objects from Mr. Chihuly’s collections rest beneath glass panes on the restaurant tables.

Across town, at the Boathouse behind Mr. Chihuly’s hotshop, the artist’s collections adorn a meeting area, the bathrooms, and nearly every room of the house. Mrs. Chihuly attributes her husband’s extensive collecting to his desire to return to a simpler time. Before he turned 20 years old, Mr. Chihuly lost his brother to a military training accident and his father to a fatal heart attack. “When I see the innocence of Dale and the collections and things, I think it was life before he lost his brother,” Mrs. Chihuly surmised. She recalled, “I never knew why Dale collected accordions. Then one time when I was at his mother’s house, we saw a photograph of his father and brother holding accordions. They played the music.”

The collections are, in Mrs. Chihuly’s estimation, a Rosebud-like key to understanding the artist. Yet instead of one sled, Mr. Chihuly has acquired thousands of objects. Mrs. Chihuly’s own work in building up her husband’s brand through canny efforts that extend to publications, institutions, films, philanthropy, limited editions, new shows, objects, and collection displays—all of which ultimately amount to significant mythmaking—can start to feel like its very own guard against loss.