How the Met Was Made

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is reopening, commemorating its 150-year anniversary with an exhibition that asks: How does this museum give an account of itself today?

Talk about a spoiled birthday. For years leading up to its 150th anniversary the Metropolitan Museum of Art had been planning a swell of celebratory programming: an overhaul of its British Galleries, debuts of major gifts of photography and drawing, new cross-cultural displays, an international symposium on collecting, a Great Hall photo op with the mayor and a big cake.

At the center of this Busby Berkeley-scaled jubilee was to be “Making the Met,” an exhibition mapping the growth and transformations of the museum’s collection. You know the rest: Days before the show’s planned opening, the coronavirus pandemic forced this museum and every other in New York to shut down, and turned the Met’s sesquicentennial into an annus horribilis.

The museum now foresees a $150 million loss in revenue for the year, and has shrunk its staff by 20 percent through layoffs, furloughs and early retirement. Shows have been delayed or canceled, budgets tightened. The Met Breuer, its four-year, hit-and-often-miss satellite, closed with a whimper; its meticulous last show, of the German painter Gerhard Richter, saw the light for just nine days.

By June, the Met’s director, Max Hollein, was apologizing for a botched statement of solidarity with Black Lives Matter after the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor ignited online arguments over museums’ past and present wrongdoings. Later that month he had to apologize again, after a senior curator misstepped on Instagram as protesters nationwide pulled down statues. Mr. Hollein, using far more direct language than his predecessors, conceded that “There is no doubt that the Met and its development is also connected with a logic of what is defined as white supremacy.”

So the museum that reopens to the public Saturday, after by far the longest closure in its history, has taken some knocks, and “Making the Met” now has to answer weightier questions. Just what kind of institution is this? How does this museum, does any universal museum, give an account of itself today?

Andrea Bayer, the Met’s deputy director for collections and administration, and Laura D. Corey, a senior researcher at the museum, have tried to craft that account with a team of hundreds, all credited by name at the entrance to “Making the Met.” Its more than 250 objects are displayed, roughly speaking, by the date the Met acquired them rather than the period or place they were made. This unusual organizing principle lets you map the growth of the Met from room to room, even as it creates strange, riveting juxtapositions across time.

The opening gallery of “Making the Met, 1870-2020.” From left: a 19th-century Mangaaka power figure from the Kongo kingdom; Vincent van Gogh’s “La Berceuse (Woman Rocking a Cradle)” (1889); Isamu Noguchi’s “Kouros”; Rodin’s “The Age of Bronze (L’Age d’airain)”; and Richard Avedon’s 1957 photograph of Marilyn Monroe.Credit...Karsten Moran for The New York Times

A closer view of the nail-studded Mangaaka power figure from the Kongo kingdom.Credit...via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Body mask, from the mid-20th century, created by the Asmat people of New Guinea. The young anthropologist Michael Rockefeller negotiated its purchase with Asmat clan leaders in 1961, and disappeared the same year.Credit...via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

For visitors returning after five months, the catholicity of these galleries will be a treat. Here is a legends-only mini-Met, which can be appreciated on the surface as a supersaturated treasure house. But in its structure, “Making the Met” is all about the ambitions and blind spots of an institution — and the changing schemes of meaning, value and interpretation that form an invisible frame around all the world’s beauty.

Those ambitions began in 1866, in a flush of American optimism after the end of the Civil War, and came to fruition four years later with the acquisition of a Roman sarcophagus. The early Met, like the nearly contemporaneous art museums of Philadelphia, Boston and Chicago, scored rather higher on aspiration than connoisseurship.

Michelangelo drawings mingle with Egyptian statuary. Burmese harps sit beside Flemish lace. The show’s horn-blowing prologue, where van Gogh and Rodin appear with a nail-studded Mangaaka power figure from the Kongo kingdom and a Richard Avedon photograph of Marilyn Monroe, testifies to the unparalleled strength and breadth of the Met’s collection, first modeled after European museums and now outclassing them.

Anthony van Dyck’s 1624 painting “Saint Rosalie Interceding for the Plague-stricken of Palermo.” A fitting work for our current time, it was among the Met’s first acquisitions.Credit...Karsten Moran for The New York Times

The earliest purchases in “Making the Met” include a fine marble bust of Benjamin Franklin, by the Revolutionary-era French sculptor Jean Antoine Houdon, but also misattributed old masters, replicas of European sculptures, and thousands of Cypriot antiquities that its first director, Luigi Palma di Cesnola, excavated with something less than scientific rigor. (Also among these first acquisitions is Anthony van Dyck’s 1624 painting of Saint Rosalia, the protectress of plague-stricken Palermo, which I was lucky to see in the first days of the pandemic.) “It contains no first-rate example of a first-rate genius,” griped an anonymous critic for The Atlantic Monthly — who turns out to have been Henry James.

But the Met was underway, and from here “Making the Met” plots the development of the collection in nine further chronological galleries, joined up by a central alley that displays projections of the museum’s old information desk, signage workshop, repair rooms.

One gallery focuses on the Met’s deep study collections of textiles, works on paper, and musical instruments, established in the early 20th century. Another zeros in on antiquities acquired through museum-financed archaeological digs of the 1920s and ’30s, when the Met would divvy up discoveries with host countries under a now obsolete legal principle called “partage.” A commanding seated statue of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut, unearthed in Egypt in 1927-28, entered the Met in this way, or at least her head and left arm did; the museum only pieced her body back together later after finding the other bits in Berlin.

The commanding “Seated Statue of Hatshepsut” (circa 1479-1458 B.C.). Visible through the window is the obelisk “Cleopatra’s Needle” in Central Park.Credit...Karsten Moran for The New York Times

The ultimate stimulators of the growth of the collection, in the first Gilded Age as in our current one, were the city’s richest: J.P. Morgan, Robert Lehman, and other financiers and industrialists who inherited the tastes, and in the best cases the noblesse oblige, of European princes. They set out to “convert pork into porcelain,” in the rather gauche words of one early museum trustee — and “Making the Met” has heaps of their finest donations, from an exquisite 14th-century mosque lamp, which Morgan gave in 1917, to a burnished 1636 van Dyck portrait of the pregnant Queen Henrietta Maria of England, which Jayne Wrightsman bequeathed to the Met upon her death last year.

Picasso’s 1913-14 “Woman in a Chemise in an Armchair,” whose disjunctive articulations of arms and breasts owe debts to West African statuary, is another new arrival; Leonard Lauder delivered it last year, part of his promised gift of Cubist painting that has beefed up the holdings of a museum once frightened of modernism.

Manet’s “Dead Christ With Angels” (1864), in which Jesus is seen hovering between life and death. Our critic calls it “one of the most staggering paintings in the whole museum.”Credit...Edouard Manet, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The transformative Impressionist gifts of the Havemeyer family (whose fortunes, a text here acknowledges, were made in the brutal sugar trade) take over nearly a whole gallery in this show. Manet’s fearlessly blunt “Dead Christ With Angels” (1864) — a Havemeyer gift in which the sallow Jesus, hovering between life and death, looms in a depthless cave — remains one of the most staggering paintings in the whole museum. Here it functions almost as an emergency brake, appearing with Courbet’s lusty “Woman With a Parrot” (1866) and one of Monet’s first plein-air riverscapes, “La Grenouillère” (1869), but also with Havemeyer donations like opalescent Tiffany vases and an impression of Hokusai’s “The Great Wave,” circa 1830-32.

An installation view of some of the Islamic acquisitions, including, from left: the end of a balustrade; on the wall, a folio from “Hamzanama (The Adventures of Hamza)”; two folios, one from the Shah Jahan Album and the other from the Shah Jahan Album; and an early 17th-century “Pierced Window Screen (Jali).”Credit...Karsten Moran for The New York Times

During World War II, several museum officials joined the effort to save, catalog and restitute art looted by the Nazis. These “Monuments Men” — and several women — included James J. Rorimer, the director of the Cloisters (and later the entire Met), whose notebook here is open to an inventory of loot he found in Neuschwanstein Castle in 1945; and Edith A. Standen, a tapestries curator and decorated military officer, who oversaw the restitution of thousands of artworks to Berlin’s state museums. She’s represented here by her stiff wool military uniform, now part of the Costume Institute.

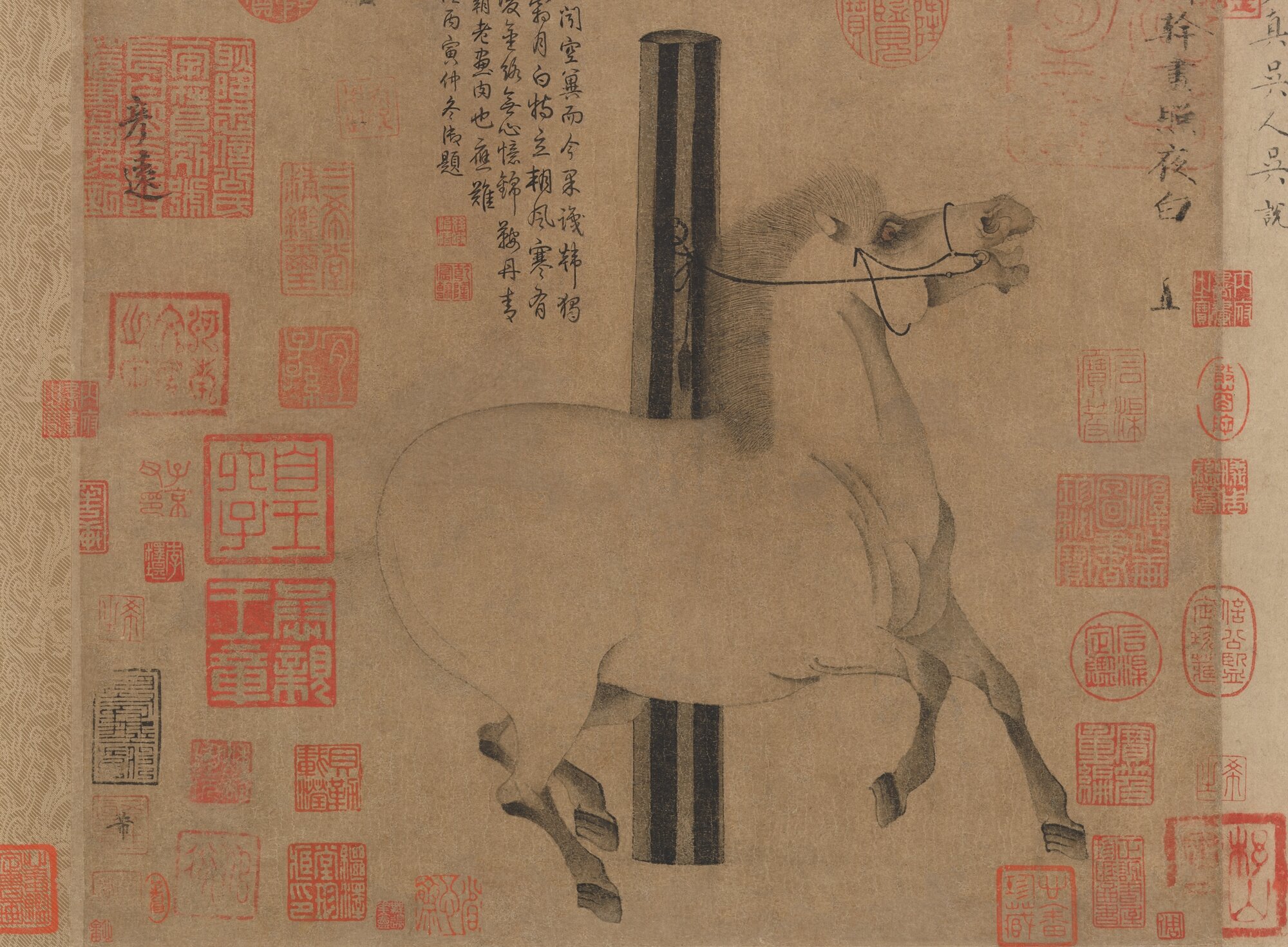

“Night-Shining White” (circa 750), a scroll painting of a bucking steed by the Tang Dynasty painter Han Gan.

Acquisitions made around the museum’s centennial illustrate the postwar expansion of the Asian collection and the Islamic holdings; the creation of the Rockefeller wing for art of Africa, Oceania and the Indigenous Americas; and a growing embrace of modern and contemporary creation. Stop before “Night-Shining White,” an energetic scroll painting of a bucking steed by the Tang Dynasty painter Han Gan, and scrutinize the white horse’s bristling mane and flaring nostrils. Examine the remarkable full-body mask, woven by the Asmat people of New Guinea, affixed with eyes of carved wood and eyelashes of cassowary feathers.

And now? The open-ended conclusion to “Making the Met” suggests a few new priorities for the museum’s departments. The European sculpture team has acquired some Venetian Judaica, the Islamic department has bought gold-trimmed headdresses for an Indonesian hajji, and the modern division owns recent works by the Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui and the Indian artist Mrinalini Mukherjee, subject of a Met Breuer retrospective last summer.

An installation of “Making the Met.” On the far back wall is El Anatsui’s “Dusasa II,” 2007.

The conclusion is somewhat baggy, but for a show about collecting that may be the point. For the Met’s primary challenge in 2020 is not what to buy. It’s how to show it, and whether a 150-year-old museum can remain nimble enough to forge new practices of research, interpretation and display.

It’s easy to identify gaps in a supposedly “universal” collection, and very easy to post anachronic judgments of what your predecessors ignored. Harder and more important is to engage with the deep structure of collecting: to understand what we value most, and how, and why, as the museum tries to chart a path from Eurocentricity to a real universalism. The Met’s holdings have globalized, to be sure. And they’re not implicated quite as directly in colonial violence as the loot-filled ethnographic museums of Western Europe. Still, if the Met’s “development,” as Mr. Hollein himself says, is “connected with a logic of what is defined as white supremacy,” then what exactly is to be celebrated at this anniversary party?

A wall case contains a dizzying array of intricate pieces, including an Islamic glass bottle, alabaster figures, and a book cover with ivory figures from before 1085.Credit...

The answer, Ms. Bayer and her team affirm in “Making the Met,” lies inside the beautiful objects themselves, in the layers of history that have accreted in the last century and a half. These works, having traveled to New York from all corners, bear memories of encounters, scars of violence, new names, new prices. They’ve been transformed as they’ve moved, and so they’re ideally positioned to map the intersections and interdependence of our histories.

But to articulate that interdependence you need to do more than fill gaps in a purportedly universal collection. You need a new “relational ethics,” in the words of the French art historian Bénédicte Savoy and the Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr, authors of the groundbreaking 2018 report on the restitution of African art. Relational ethics means recognizing that what the museum once called “universal” was one specific worldview — not to be scrapped wholesale, but to be absorbed into a global network of other tactics, other approaches, other voices.

Relational ethics means treating objects of the collection not as static objects of beauty, but vectors whose meanings and values change as they circulate among peoples — as the Met did in “Interwoven Globe,” its unbelievably intelligent textile exhibition of 2013. It means opening new circuits of research and collaboration that stretch well past 1000 Fifth Avenue — as the Met has done in its current knockout show “Sahel,” whose curators worked with colleagues in Senegal and Niger. Relational ethics means something much deeper than a box-ticking exercise; it means elaborating the humanism that the Met supposedly stands for to its fullest, most global extent.

Reformists inside our universal museums now promise “inclusion.” Radicals outside them prefer “decolonization.” But both of those objectives will come to naught, as Ms. Savoy and Mr. Sarr understood, unless we see culture as an infinite chain of differences, which always defies the binary oppositions we’ve inherited from the age of empire, colonialism and encyclopedic collecting. The Met in 2020 has the potential to be an exemplar of this relational ethics, and to place the Mangaaka statue, the Michelangelo drawing, the Marilyn Monroe photograph within a web of lived relations — where all of us, at all times, from all places, find our reflections in the art of all peoples. It is the only metropolitanism worth the name.