Early Works by Edward Hopper Found to Be Copies of Other Artists

Nytimes_Most grad students in art history dream of discovering an unknown work by whatever great artist they are studying. Louis Shadwick has achieved just the opposite: In researching his doctorate on Edward Hopper, for the storied Courtauld Institute in London, Mr. Shadwick has discovered that three of the great American’s earliest oil paintings, from the 1890s, can only barely count as his original images. Two are copies of paintings Mr. Shadwick found reproduced in a magazine for amateur artists published in the years before Hopper’s paintings. The reproductions even came with detailed instructions for making the copies.

Mr. Shadwick spells out his discovery in the October issue of The Burlington Magazine, a venerable art historical journal.“It was real detective work,” Mr. Shadwick explained, Zooming from his sunny apartment in London. At 30, he’s older than most of his graduate-school peers because of a longish spell fronting an alt-rock trio (White Kite), a past not revealed in the blue button-down he wore when we talked and his close-cropped dark hair. Mr. Shadwick was working out the earliest influences on Hopper’s art — one aspect of his Ph.D., half-finished so far — when he figured out that an American Tonalist painter named Bruce Crane (1857-1937) might have played some kind of role.

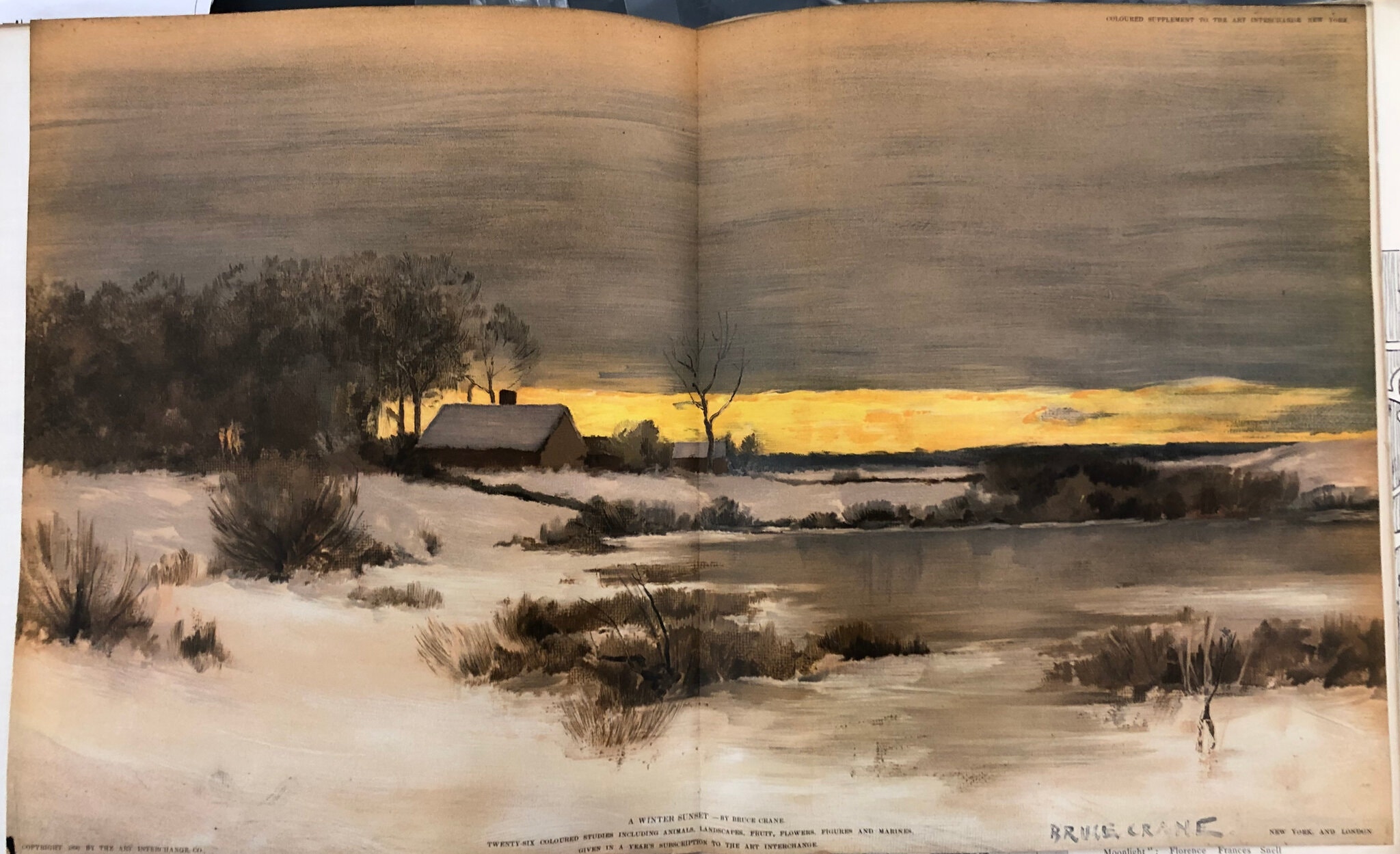

Then, early this summer, in what Mr. Shadwick called a “eureka moment” of pandemic Googling, he landed on “A Winter Sunset,” a painting by Crane from an 1890 issue of The Art Interchange that was an almost perfect match for one of Hopper’s teenage works, long known as “Old Ice Pond at Nyack,” circa 1897, depicting a winter landscape with a streak of waning light. (A gallery is selling it now, with a price estimate of $375,000; the change in its status might affect buyers’ offers.) Mr. Shadwick went on to discover similar sources for all but one of Hopper’s first oils.

Scholars have talked about those early Hoppers as showing us his childhood home in Nyack, N.Y., and as examples of his preternatural talent as a self-trained young painter, “and actually, both these things are not true — none of the oils are of Nyack, and Hopper had a middling talent for oil painting, until he went to art school,” said Mr. Shadwick, adding, “Even the handling of the paint is pretty far from the accomplished works he was making even five years after that.” Those weak brush-skills are now the only thing in those earliest oils that anyone can lay claim to as Hopper’s.

“It’s always great to find out something new about a major artist,” said Carter Foster, deputy director at the Blanton Museum of Art, in Austin, and a Hopper expert who organized the landmark show of his drawings at the Whitney Museum in 2013. He got to know Mr. Shadwick’s work after meeting him at a Hopper symposium and admires the depth of the archival research involved. He also admitted that the discovery did not come to him as much of a surprise, given that, before the advent of modern art and its freedoms, artists almost always got their start by copying.

For Kim Conaty, curator of drawings and prints at the Whitney Museum in New York, where she is at work on a big Hopper show, the copying that Mr. Shadwick revealed has more important repercussions: “It cuts straight through the widely held perception of Hopper as an American original,” she said — as an artist whose innate genius allowed him to emerge on the scene without a debt to others. “The only real influence I’ve ever had was myself,” he once claimed.Ms. Conaty said that Mr. Shadwick’s discovery promises to be “a pin in a much broader argument about how to look at Hopper.” Mr. Shadwick is building precisely such an argument in his doctorate; the parts I’ve read look very promising.

Mr. Shadwick submitted his discovery about Hopper’s early oils to the Burlington Magazine for peer review, according to Michael Hall, its editor. It was part of a larger project meant to spell out the cultural context from which the painter evolved — “the things he was seeing, the things he was reading, the newspapers his family received, the journals,” Mr. Shadwick said.

A Londoner, he especially wants to understand the notion of “Americanness” that Hopper grew up around, and that then grew up around Hopper as his reputation matured; it still rules much of the talk about him. But we’re more likely to assume or assert that Hopper and his art are quintessentially American than to ask ourselves what that meant for him and his audience, or what it might mean for us today.

In our new century, when the country’s place in the world seems less sure by the day and when even Americans are split on the state of their nation — does it need to be made great again or does it need to face up to past failures? — a “national” treasure like Hopper seems to beg for a fresh approach.

“What is this Americanness that people are identifying? Where does it come from, is it useful as a term?” — Mr. Shadwick said those are the questions at the heart of his study of Hopper. Maybe it takes someone from elsewhere to recognize just how artificial and peculiar American identity has been, and how directly Hopper was involved in constructing it in his persona and his work.

“Yes, there’s a lot of talent and beauty and all that,” said Mr. Shadwick, who remains a big Hopper fan, “but there’s also a very conscious awareness of his place in history, and of the purported Americanness of the scenes he was painting.”

Moving on from copying, the young Hopper spent a long spell in art schools in New York and then flirted for a while with modern French styles and subjects. But when a 1915 show of his Frenchified paintings got panned, while a single New York cityscape earned praise, Hopper knew where to head next: “He refines and refines and refines these ideas of what it means to be an American painter,” Mr. Shadwick said.

As the United States withdrew into itself in the period between the world wars, an “Americanist” tendency took stronger hold than ever in the country’s high culture, Mr. Shadwick explained, “and Hopper played along with it. Hopper knew exactly what he was doing for the market for his work.” As Mr. Shadwick writes, in thesis-ese, Hopper’s “centring of the white male Anglo-Saxon American experience, his regionalist sympathies for New England, and his eventual aversion to European-style modernism,” can all be connected to thoughts and feelings about the United States that were widely held in his day.

ne aspect of this “Americanness” involved the image of the lone male — tall, taciturn, remote, just like Hopper — bravely forging his own path. This was precisely the image of himself that Hopper helped to propagate; even after his death, it went on to shape the story, now revealed to be a myth, of the miraculous early oils that Hopper is supposed to have come up with on his own. Mr. Shadwick’s discovery about those first paintings may also illuminate Hopper’s much later, most iconic masterpieces. Critics and scholars have always been intrigued by an awkwardness that Hopper allowed himself in many of his classic paintings: seas that look more painted than liquid in his famous “Ground Swell”; the awkward anatomy of his female nude in “Morning in a City” or the stony faces of the diners in “Nighthawks.”

Now that we know that Hopper was never a painting prodigy, we can think of his later paintings as deliberately revisiting the limitations of his adolescence, and finding virtue and power there. That’s a classic move in American culture: To see the unschooled and homespun as more authentic — and especially as more authentically American — than the sophistries of those decadent old Europeans.

In rendering his pioneering views of everyday life in average America (or, as Mr. Shadwick would say, in the America Hopper helped define as average), Hopper chose an everyday style that brings him closer to the modest commercial illustration of his era than to the certified old masters. It’s as though, to be truly in and of their time and place, and fully “American,” paintings of a city’s simple shopfronts, or of plain women in plain rooms, had to be rendered in a plain manner worthy of their subjects, or as unworthy as them.

If Hopper claimed to be an absolute original, uninfluenced by others, his greatest paintings work hard to convey a different image of their maker: Their studied awkwardness asks us to imagine him as someone who might indeed have started his career copying someone else — as just your average American, working hard to make good.