Archigram and the Dystopia of Small-Scale Living Spaces

Archdaily_Until recently, the origins of the tiny-house movement were of little interest to the scientific community; however, if we take a look at the history of architecture and its connection to the evolution of human lifestyles, we can detect pieces and patterns that paint a clearer picture of the foundations of this movement that has exploded in the last decade as people leave behind the excesses of old and opt for a much more minimalist and flexible way of life.

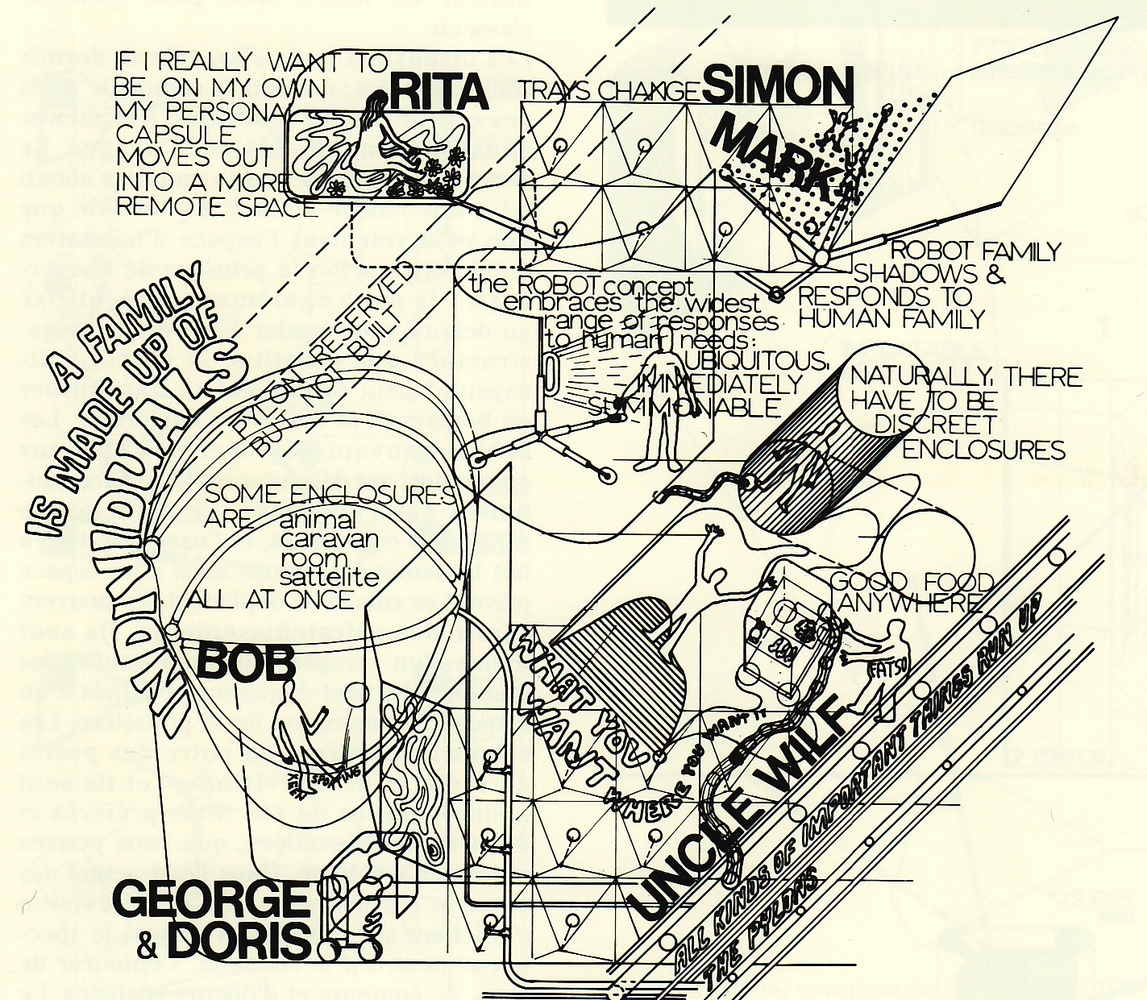

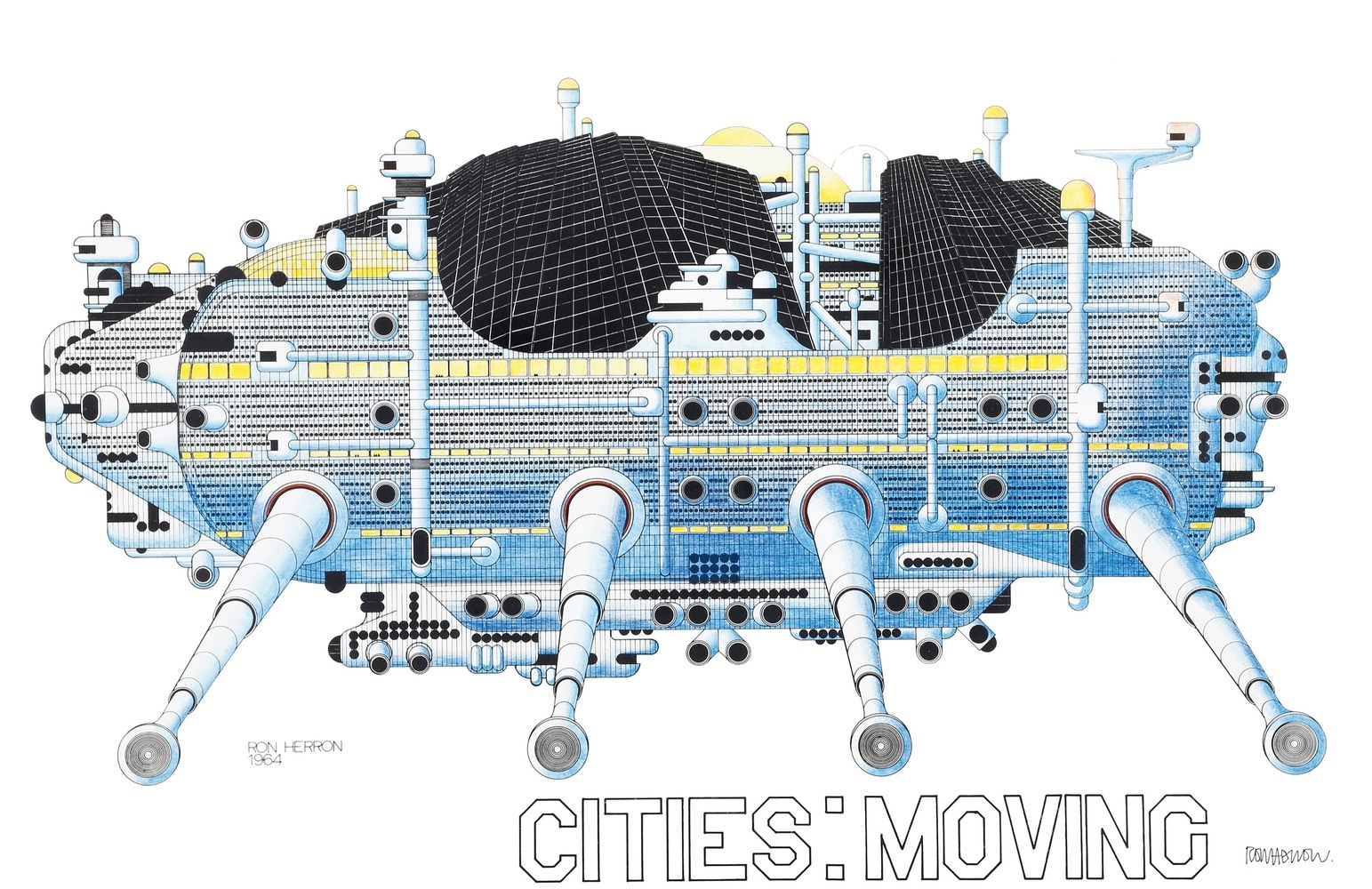

One such example is Archigram; an architectural collective consisting of Peter Cook, Jhoana Mayer, Warren Chalk, Ron Herron, Dennis Crompton, Michael Webb, and David Greene who turned their focus on the radical post-war utopias, a movement that awakened in Europe at the time. Some of the collective's most notable projects include The Plug-In City, The Walking City, and The Instant City. Each one incorporated a graphic style hallmarked by bright colors and a futuristic and glamorous aesthetic that demonstrated a effervescent and constantly transforming urban paradise.

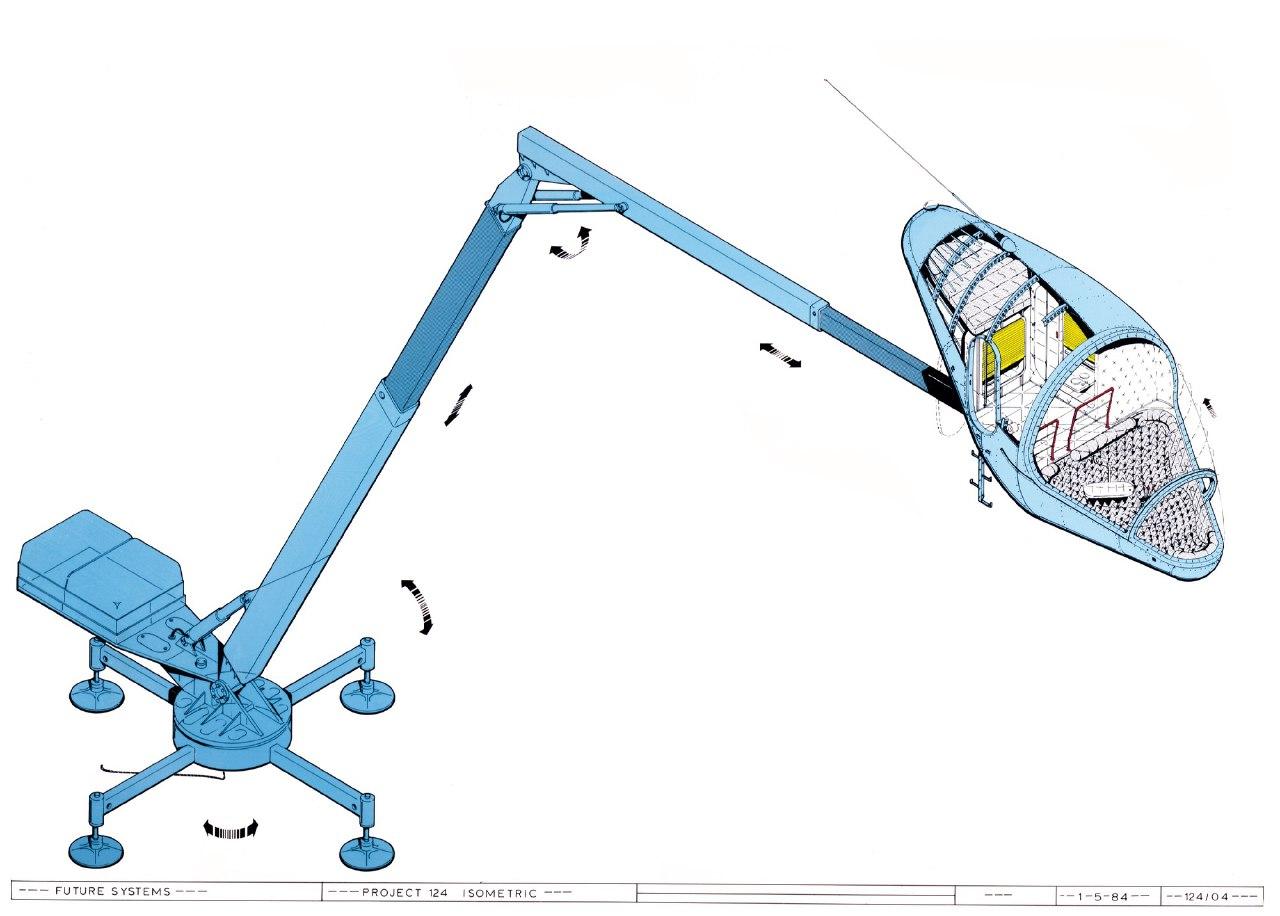

Although these illustrations focused on urban living and collective, rather than individual, spaces, they never lose sight of personal living quarters, as noted in their diagrams. Probably the best known is Capsule Houses (1964) a set of prefabricated and easily assembled homes. These modules consisted of small circular structures connected to a central macrostructure and were the central feature of The Plug-In City project.

This setup requires that social interactions happen outside, in the common spaces, and establishes a new territorial layout that responds to the need to socialize at that moment. This laid the groundwork for a city that could walk and visit new places, which doesn't seem so bizarre if we think about the globalized world we inhabit today. Archigram's vision of walking, plug-in cities made up of minimalist housing capture the modern-day desire to integrally restructure the economy, society, and our overall way of living in a bid to save space and resources.

As Kaley Overstreet illustrates in her article "The Life and Death of the Tiny Home Trend", we can see that certain ideas that once seemed promising, attractive, and even, utopic, soon found themselves pitted against the reality of cities that, not only were in the process of reinventing themselves, they were building upon their own ruins so to speak. In the last decade, the trend flooded everything from magazine covers to television programs, hawking minimalist principles under the idea of freeing oneself from the confines of materiality in favor of a lifestyle bordering on the nomadic.

This awakened interest based on economic terms and developers saw an opportunity to build more with less with little thought for quality of life of the user. The result was living spaces that adhered to the principles of minimalism but with none of the luxury, freedom, or flexibility that characterized the Tiny House movement. With few people opting for the bare-bones lifestyle offered by these developments, entire city blocks were reduced to ghost towns as shown by Jorge Toboada in his series of photographs titled High Density.

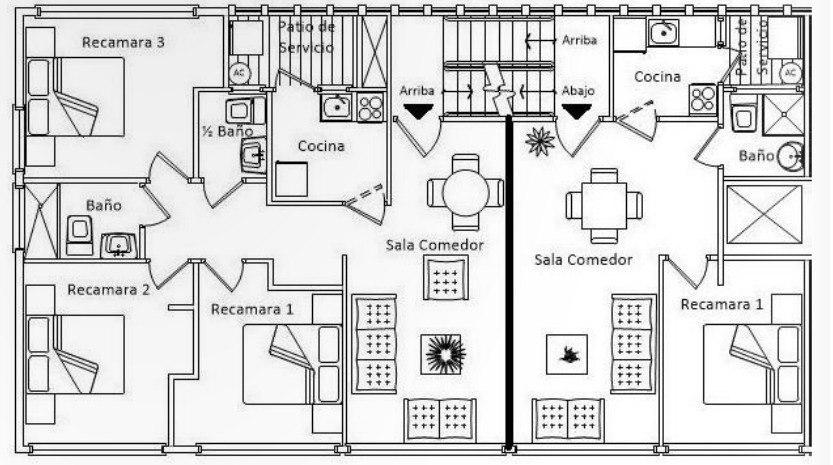

Undoubtedly, these minimalist principles have offered much-needed lessons on organization and space utilization and have demonstrated the importance of weighing the pros and cons of every idea ever put into a blueprint. This brings us to the realization that every action has a consequence in the construction (or deconstruction) of urban models, as has been demonstrated many times over throughout Latin America. We can see this in the work of Mario Pani and the first functionalist buildings of Mexico City such as the Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán, or the apartment buildings in Tlatelolco, where the spaces, although small, were designed to take advantage of every square foot available. This became the model for Mexican urbanization; however, it was not without its difficulties as explained by architect and muralist Juan O'Gorman:

Functionalism reduces us to our most basic necessities, completely ignoring the importance of satisfaction and pleasure taken in one's living space. For an architect, this is unacceptable. In essence, functionalism in architecture is mechanically rational but humanly illogical.

— Interview with Juan O’Gorman by Olga Sáenz taken from: Rodriguez, Ida et al (compilers). The words of Juan O’Gorman. Institute of Aesthetic Research. Mexico. 1983. (pp.20)

In spite of this, in recent years, the tiny house trend has offered tools to expand living spaces in Mexico that struggled to meet the needs of modern living, as illustrated in the project Un Cuarto Más / Taller ADG and One More Room/ ANTNA. The project offers a much more realistic and contextualized view of a living space that adheres to functionality while heeding modern needs and tastes.