Lee Krasner on How to Be an Artist

artsy_Support didn’t come easily to Lee Krasner. Compliments of her early work were laced with blatant sexism: “This is so good you wouldn’t know it was done by a woman,” Hans Hofmann

told her in 1937, while teaching Krasner at his art school. Other mid-20th-century art-world gatekeepers, like Clement Greenberg and Peggy Guggenheim, disregarded her work completely. But Krasner’s will to paint was stronger than any snubs, and she persevered in making some of the mid–20th century’s most spellbinding and tempestuous Abstract Expressionist compositions.

Krasner passed away in 1984, and the interviews she left behind were conducted primarily in the last 20 years of her life—after she finally emerged from behind the hulking shadow of her husband, drip-painter Jackson Pollock. Across these conversations, Krasner chronicled the hurdles she faced and the inspirations that drove her work. Below, we highlight several words of wisdom from the boundary-pushing painter. They touch upon the importance of persistence, spontaneity, failure, and risk.

Lesson #1: Fight for a place for your work

Lee KrasnerUntitled, 1942

"Women of Abstract Expressionism" at Denver Art Museum, Denver

Krasner’s bid to be taken seriously as an artist began early. Born in Brooklyn, she began studying applied arts at an all-girls’ high school in Manhattan in 1921 at around age 13. She then attended Cooper Union’s women’s school, the Art Students League, the National Academy of Design, and finally, Hofmann’s School of Fine Arts. Krasner also became passionately involved in activist efforts that championed artists’ rights. As a member of American Abstract Artists in the late 1930s and ’40s, she poured energy into promoting abstract art (still a vanguard movement at the time) and demanding more exhibition opportunities for its artists. In a 1964 interview with Dorothy Seckler, Krasner recalled picketing in front of the Museum of Modern Art during a trustee meeting. The group’s demand was straightforward: show more American artists, instead of giving consistent priority to their European counterparts. Krasner pushed leaflets bearing the bold demand to “Show American Paintings” on board members as they exited the building.

Around the same time, Krasner joined the WPA’s Federal Art Project, a wartime effort that hired artists to swathe the country in public art and, in turn, help boost the faltering economy. For one mural, Krasner led a team of 10 men. She also became a vociferous member of the WPA Artists Union (alongside the likes of painter Arshile Gorky

and critic Harold Rosenberg), which meant “more meetings and fighting for artists’ rights,” as she recalled in the same interview. These efforts were time-consuming, but they ultimately offered the burgeoning painter more space and support to make art. “I would say it gave me an opportunity to continue through a period [when] one had a livelihood to deal with,” she remembered. “This allowed for painting and I’d say, in that sense, it was extremely influencing.”

When it came to combatting the art establishment’s deep-seated sexism, Krasner’s approach was more subtle. “I couldn’t run out and do a one-woman job on the sexist aspects of the art world, continue my painting, and stay in the role I was in as Mrs. Pollock. I just couldn’t do that much,” she recalled with candor in Cindy Nemser’s 1975 book Art Talk: Conversations with 12 Women Artists. Instead, Krasner played the long game, focusing on her practice and slowly but determinedly establishing a space for her work amongst her male peers. “What I considered important was that I was able to work,” she continued. “You have to brush a lot of stuff out of the way or you get lost in the jungle.”

Lesson #2: Welcome new directions

"Women of Abstract Expressionism" at Denver Art Museum, Denver

Throughout her painting practice, Krasner welcomed change with gusto. In the early 1940s, just after studying with Hofmann, her canvases swayed with geometric forms that “gave Cubism a rhythmic swing,” as writer Claudia Roth Pierpont has pointed out. In 1940, during a walkthrough of the fifth annual American Abstract Artists exhibition, master abstractionist Piet Mondrian also commended the “very strong inner rhythm” of these works. Despite positive feedback, Krasner hungrily explored other styles, searching for an aesthetic that more powerfully harnessed her emotions.

Krasner had her first significant “break”—her word for the stylistic shifts in her practice—after meeting Jackson Pollock in 1942. The two artists fed off each other, and by 1946, Krasner began her “Little Image” series. The small compositions are packed tightly with bursts of symbols and repetitive strokes; she long touted them as her best work.

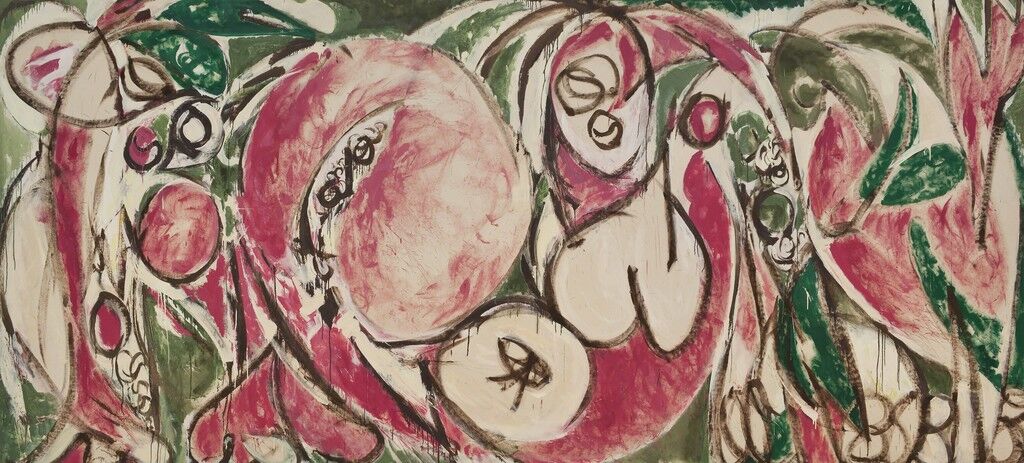

Krasner embraced—even celebrated—these periodic reinventions. She believed they set her apart from her contemporaries, many of whom stuck doggedly to a single style. “I find myself working for a stretch of time somewhere between four and five years on something and a break will occur [in the] imagery and I have to go with it,” she explained in the 1964 interview, “so in that sense I find it a little off-beat compared to a great many of my contemporaries.” Over time, her canvases expanded, and the forms that filled them fluctuated from sharp and splintering (as in Burning Candles, 1955) to undulating, pneumatic, and decidedly feminine (as in The Seasons, 1957, and Gaea, 1966). “There’s been many other transitions in my work, and I expect that as long as I continue painting,” she continued. “By now I accept that this is the way it moves for me.”

Likewise, Krasner delighted in unexpected changes that occurred during the process of painting itself. “I’m not interested in a prior theory when I paint my picture, because I think you get an awful lot of dead painting, not interesting, dead, sterile,” she told Seckler. “Well, that’s not very exciting, for heaven’s sakes. One wants to discover.” She allowed the action and rhythm of painting to take over, responding instinctively to unanticipated gestures or forms. “The minute you begin to say it can’t do this and it’s got to do that and it can’t do the other, well, it’s pretty boring stuff,” Krasner continued. “And you’re certainly not allowing for discovery of any kind. You’re cutting that source quickly.”

This often manifested in decisions related to her palette. “Color for me is a very mysterious thing. I might say I haven’t done anything in blue, I’m gonna use blue, but then it’s like it comes out green or Alizarin crimson or something,” she explained in a video interview. “I’m aware of that, I’m conscious of that kind of thing, but I don’t try to change it. I don’t say it’s got to be blue. And I insist on letting it go the way it’s going to go rather than forcing it.” In Krasner’s views, these moments of “letting go” powered her best paintings, not to mention her own happiness. Miraculous things happened, she liked to say, when “you aren’t rigid with some fixed idea before you go into your studio of what a painting should be…because it seems to take all the joy out of living.”

Lesson #3: Revisit failed work

Lee KrasnerMilkweed, 1955

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

Lee KrasnerBurning Candles, 1955

American Federation of Arts

Krasner described her process as a pendulum: “It seems to swing back to something I was involved with earlier, or it moves between horizontality and verticality, circularity, or a composite of them,” she said in a 1973 catalogue published by the Whitney Museum of American Art. “For me, I suppose that change is the only constant.” Indeed, Krasner often returned to past work, reinventing failed projects as new, fervent compositions.

Krasner’s torn paper collages boldly evidence this habit. In several interviews, she described their origin story with the pride of having fixed something terribly broken. “I did a batch of drawings, I had them pinned up in the whole studio, I went in one day, I hated them, and I tore them all up and threw them on the floor,” she recalled in an interview. “When I went into the studio again, which was several days later, they looked pretty good that way.” In Krasner’s hands, a group of failed drawings transformed into an important facet of her practice—one that informed the spatial and compositional structure of her paintings, as well. “This seems to be a work process of mine: I’m constantly going back to something I did earlier, remaking it, doing something else with it, and coming forth with another more clarified image possibly.”

From then on, Krasner consistently revisited unsuccessful or unresolved work with fresh eyes, and in many cases, these discards stimulated new stylistic and conceptual directions. “I started going through a lot of work that dissatisfied me in the same process,” she told Seckler. “Destroying in order to recreate.