The 5 Biggest Changes to Look for at the New MoMA

artsy_It’s a daunting proposition to rejigger one of the Western world’s most famous modern and contemporary art collections. On October 21st, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) will reopen to the public after a summer of major renovations, re-evaluations, and over five years of architectural planning by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Gensler—a $450 million, multi-stage project that ultimately added 38,000 square feet of gallery space, mostly in the new David Geffen Wing. This updated MoMA will allow for around 2,400 works to be on view at any time, around 1,000 more than the building previously supported.

The esteemed institution took major risks in reconceiving galleries long devoted to crowd-pleasing favorites. If you’re an art educator accustomed to bringing your students to the same room, year after year, to see Pablo Picasso’s revolutionary painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), you may need to check the museum’s website (or on-site monitors) to discover where the painting will be hanging. Curators plan to switch up permanent collection installations every six months by reconceptualizing individual rooms, shifting entire presentations, or using other strategies to encourage new perspectives on modern and contemporary art.

Exterior view of the Museum of Modern Art, Blade Stair Atrium, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Gensler, as a part of The Museum of Modern Art Renovation and Expansion. Photo by Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Interior view of the Museum of Modern Art, Blade Stair, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Gensler, as a part of The Museum of Modern Art Renovation and Expansion. Photo by Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

At most, that’s a tiny inconvenience compared to the potential benefits of the new system, which is intended to leave art history open-ended. As MoMA’s director Glenn Lowry stressed at a press preview on Thursday morning: “What makes modern and contemporary art exciting is precisely the debates and arguments that are still taking place.” Instead of proposing that they have the last word, the new MoMA undermines the idea that a single narrative about so many artists, working across so many years and countries, could ever exist.

Museum expansion projects are never perfect, and MoMA’s latest revamp is no exception. There will always be gripes—does the wall text dumb down the content of the work? How much corporate money is too much? How should the museum handle the scandal around board member Larry Fink? But as you lose yourself in the new and renovated galleries and find a number of artists and presentations you’ve never before encountered at MoMA, don’t be surprised if you become entirely enchanted.Here are five of the most remarkable changes to the museum.

The big rehang

Pablo Picasso. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon . 1907. © 2004 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

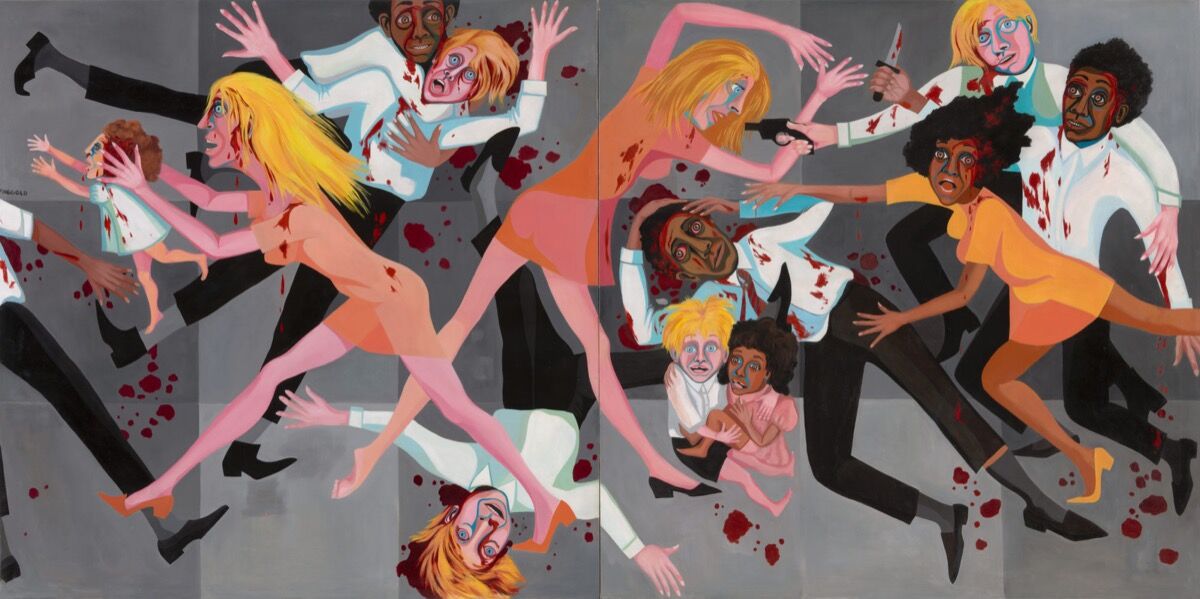

One of the most brilliant features of MoMA’s rehang of its permanent collection is a winning juxtaposition of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and a 1967 painting by American artist Faith Ringgold, American People Series #20: Die. The subtle violence of Picasso’s picture, embedded in his fractured depictions of sex workers’ bodies and appropriated African masks, becomes explicit in Ringgold’s: She painted a gory, blood-spattered scene of well-heeled men and women, both black and white, in the aftermath of a shooting and stabbing. Ringgold has cited Picasso’s influence on her work, and the new hang allows viewers to make connections between two artists born 50 years apart, on different continents.

In addition to creating enlightening connections, the rehang also attempts to eliminate hierarchies across media. You can find George Ohr’s ceramic bowls in the same room—gallery 501, “19th Century Innovators”—as Vincent van Gogh’s iconic painting Starry Night (1889). Gallery 420, “War Within, War Without,” features Philip Guston’s 1975 painting Deluge II, as well as David Hammons’s body print Pray for America (1969) and a number of Adrian Piper photographs. All consider the effects of global warfare, from very different perspectives.

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #20: Die, 1967. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

To organize gallery 514, titled “Paris 1920s,” MoMA’s chief curator of painting and sculpture Ann Temkin worked with curators from different departments to select prints, photography, and a funky, modernist Man Ray

chess set to fill the gallery. Photography curator Sarah Meister suggested photographs by Germaine Krull and Florence Henri, which now hang next to Picasso’s The Studio (1927–28) and across from Constantin Brancusi’s sculpture Blond Negress II (1933, after a marble of 1928). The gallery also houses The Moon (1928) by Tarsila do Amaral, a Brazilian artist who also lived and worked in Paris in the early 20s. According to Temkin, MoMA recently deaccessioned a painting by Fernand Léger in order to acquire the do Amaral work and many others by “pioneering women modernists.” Léger is also represented in the gallery with three works.

Installation view of, Paris 1920s (Gallery 514), at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar. © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art.

What all the galleries aim to capture now, according to Temkin, is “that sense of interconnection and vitality” among artists from around the world, practicing myriad disciplines, who worked in communities grounded in specific places and times. She hopes that by reuniting all these artists a century later, viewers “get to feel some of the sparkle and electricity” of that moment.

Finally, many visitors getting reacquainted with MoMA in the coming months will rejoice to see Lee Krasner’s paintings hanging in the same gallery as one of the museum’s most famous Jackson Pollock drip canvases, One: Number 31, 1950 (1950). This pairing may change in six months, but hopefully future gallery revisions will be equally winning. “The museum itself is not just a work in progress, but it’s constantly questioning itself,” said Lowry. Questions, he noted, are more interesting than answers.

A new way to view performance

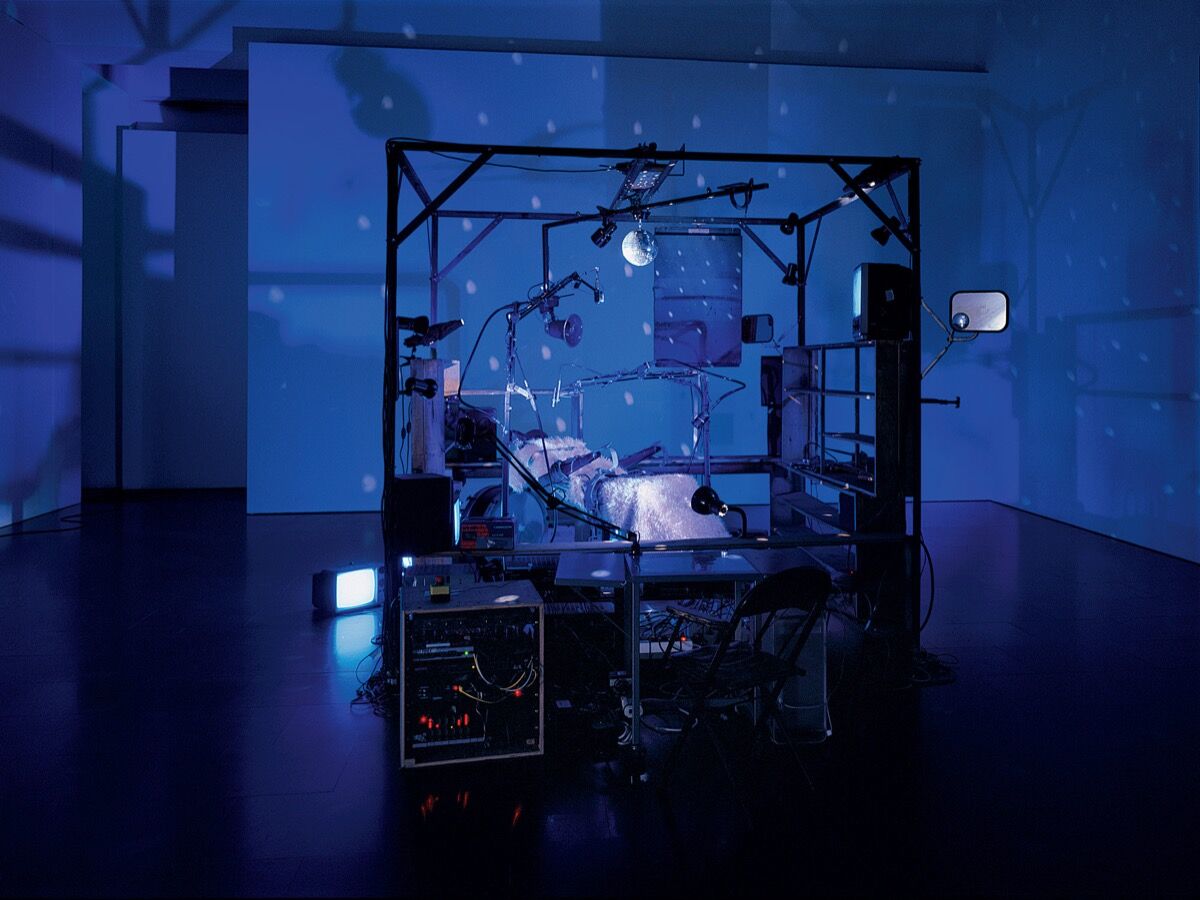

Installation view of David Tudor, Rainforest V (variation 1), 1973/2015, at the Museum of Modern Art, 2019–2020. Photo by Heidi Bohnenkamp. © 2019 David Tudor and Composers Inside Electronics Inc. Image © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art.

Exhibiting performance art is tricky. Museums and galleries often attempt to capture the spirit of radical dances, scores, and happenings long after the artists themselves have passed away and the exhibiting context has changed. Going to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and seeing photographic documentation of a half-dressed man lying under a ramp, for example, is very different from walking into a SoHo gallery in 1972 and knowing that an artist is masturbating under the floorboards.

MoMA offers a solution to this conundrum with its new Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Studio, on the fourth floor of the museum. A dark floor, black walls, and a massive, wall-sized window looking onto gridded skyscrapers distinguish this space from the blond wood-floored galleries nearby. The space will house experimental and live work, ranging from music to film. Chief curator of media and performance Stuart Comer compared the space to Yoko Ono’s loft, which he said served as a “crucible” for radical artwork in the mid–20th century. The studio will be less about “grand spectacle,” he said, than about “direct, intimate engagement with how artists work.”

For the opening, David Tudor and Inside Electronics Inc.’s Rainforest V (variation 1) (1973–2015) will be on view. The piece is both sound-based and visually stunning. It comprises everyday objects, ranging from black buckets to a wood plank, all suspended from the ceiling. Each produces a different noise thanks to sound transducers that, as Comer put it, “make each object a voice.” He said he’s hoping the space allows for “more dynamic engagement” through “experiential installations.”

A new (old) kind of film

Anny Aviram and Kate Keller, The Departure of Guernica. 1981. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Rajendra Roy, MoMA’s chief curator of film, believes this fall’s exhibition of home movies and amateur films, titled “Private Lives Public Spaces,” may be the first of its kind at a “non–film exclusive museum.” The movies, all part of MoMA’s permanent collection, will screen in the newly renovated Yoshiko and Akio Morita Galleries. The biggest change to the film lineup this season, Roy said, is that most of the programs are collection-based, “to align with the rest of the museum.”

The offerings are broad in scope, with many featuring little-seen or unseen footage of famous figures. Home movies by James Joyce (1935), Salvador Dalí

(1954), and Aaron Copland (1938) will be on view, in addition to three minutes of footage showing Cindy Sherman, back in 1976, with a bird. Another segment of the programming will focus on the museum itself: Dismantling of the Andean Exhibition, from 1954, and Moving Day at the Museum, from 1937, promise nostalgia and insight into the inner workings of a long-gone MoMA.

Creativity at the center

Installation view of “Taking a Thread for a Walk,” at the Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Denis Doorly. © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art.

The Paula and James Crown Creativity Lab, on the museum’s second floor, will house all-ages educational programming. Artmaking stations—which will change as the museum’s programming shifts—are currently set up with looms to encourage nascent weavers and pencils and paper for visitors to “create a map representing where you are,” as the station’s instructions put it. The education department connects these activities to the temporary exhibition “Taking a Thread for a Walk.” Located in the Philip Johnson Galleries, the show features woven work by Anni Albers, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Le Corbusier, and many more.

To gain inspiration for the new education space, architecture firm Gensler toured artists’ studios around New York City. The architects were particularly drawn to Brooklyn’s Pioneer Works, which features a large exhibition and performance space on its ground floor and studios on upper floors. At MoMA, they hope the Creativity Lab is an intimate oasis away from the large atrium, which is sure to be packed as soon as the museum opens.

“The whole idea is the space is about flexibility,” said Erin Ryder, a Gensler representative. A wall swivels around in an arc, able to create a partition if needed. All the furniture is stackable, and cabinets are elegantly hidden within wooden-paneled walls.

One of the first visiting artists working in the space will be Francesca Rodrigues Sawaya, who integrates ideas about storytelling and coding into her woven work. Another program, dubbed “Six Degrees,” will involve staff asking visitors to draw connections between six objects from MoMA’s collection.

Great new shows

Installation view of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, The Killing Machine, 2007. Photo by Seber Ugarte & Lorena López. © 2019 Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller. Courtesy of the artists and Luhring Augustine, New York.An inaugural lineup of excellent temporary presentations will entice visitors out of the permanent collection galleries. “Betye Saar

: The Legends of Black Girl’s Window” is a haunting presentation of the Los Angeles artist’s assemblage sculptures and prints. Full of tarot references and brimming with Saar’s unique brand of spirituality, it’s a perfect Halloween exhibition and a long-overdue exploration of a career spanning over five decades.

On the museum’s sixth floor, the special exhibition “Surrounds: 11 Installations” unravels through 11 large galleries featuring 11 immersive experiences, each with a different contemporary artist or duo. The roster—which includes Arthur Jafa,Hito Steyerl, Sheila Hicks, and Sarah Sze—is formidable. The eeriest presentation is by Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller. As you enter their gallery, an attendant will smile and say: “Welcome! This is The Killing Machine.” Press a red button and watch some robots remind you of your worst-ever dental experiences.